Hello, friends,

I hope you enjoy this piece. I particularly loved writing this one. It made me feel very alive.

I want to say a huge thank you to my dear friend

/Joseph Rizzo Naudi, who put up with me locking myself away to work on this while he was staying last weekend, and also let me read the whole thing down the phone to him while he was trying to go to a party on Friday, and even made suggestions that vastly improved it. What a gem. I’m extremely lucky to have friends who understand my obsessions.It’s fairly long, so as usual, I’m including a voice recording that you can put on in the background while you do the dishes. Which is, as I hope you’ll soon agree, a wildly complex and beautiful act of sculpting reality.

Love,

x Eleanor

I was chatting to a new philosopher friend a couple of weeks ago. We’d been talking about writing and the nature of reality—you know, the usual stuff—when he said something that made me shout “YES!”. He told me that he encourages his students to approach their work, and their lives, as though they’re painting an oil painting, not completing a jigsaw puzzle. Meaning (and this is my very liberal paraphrase): Try not to trick yourself into believing that there’s a picture on some box somewhere, a way things are or should be, and that your job is to assemble it correctly or puzzle it out. There is no picture on the box, no answer to the question of life. The task is to take the raw materials in front of you—the ocean of information and experience that is The World—and use them to paint the picture you want to live in and gift to others.

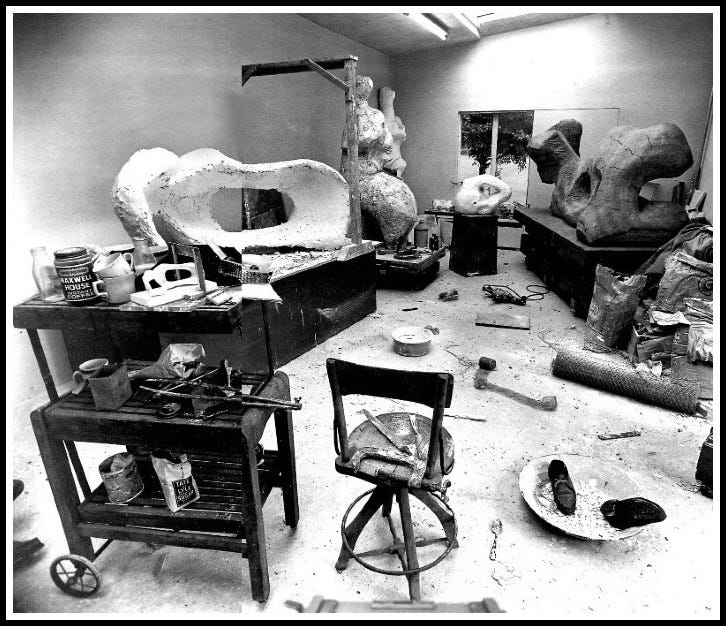

There is no picture on the box. There’s only the oil painting you make, day by day. And in fact, I would extend the metaphor. I would say that more than an oil painting, reality is a sculpture. A work of art that we make with all our senses and our whole bodies.

(The philosophers among you might have guessed that there’s all sorts of Kant and Heidegger going on underneath this analogy, but friends, we have a lot to get through, so I’m going to keep moving forward.)

I’ve seen a lot of dire articles lately about how AI is affecting the work of college students; about how much thinking is being outsourced to ChatGPT, and the effect this seems to be having on attention and engagement and honestly the will to live (mine, at any rate). This analogy of completing a jigsaw puzzle vs turning your life and learning into a sculpture is the most inspiring and succinct argument I’ve heard against that way of studying. After all, if life is a jigsaw puzzle and we just have to find the answers and piece them together, it’s someone else’s picture we’re working to. And to whom, exactly, have we handed that power?

But this isn’t a lesson for students alone. If students are over-relying on AI, that’s because our whole culture is fucked all the way up. AI itself is just a direct and obvious extension of a mistaken belief that modern, Western culture has been deepening into for at least half a millennium.

The ideology of scientism (which doesn’t really reflect the often intuitive and imaginative practice of science) has, for 500 years, been telling us that material reality is a jigsaw puzzle that we solve with our analytical and “detached” observational skills, and that imagination and creativity are luxuries, nice extras.

What a crock of shit. To be human is to create. As a function of being incarnate and sentient, we are at all times creating an image, a sculpture, out of infinity, because that’s the only way to get from sunrise to sundown without melting into bafflement. The world isn’t divided into trees and tables and Burger King and hairdressers. It’s an ocean of pure being, including (as confirmed by physicists—but we’ll get onto that) intimations of realms beyond our material reality. That ocean of pure being is the raw material. The clay. We take it and form the sculpture, all day every day, as the first and most essential act of our existence—taking, for instance, a particular collection of light waves, and laying the word “green” on it, and then layering on top of that all of our personal and cultural associations with the colour green, and all of this done in all of the senses at once, so that while we’re labelling light waves “green” we’re also labelling and associatively layering, say, May warmth and a distant sound we assume to be a train and the smell of wild garlic, and all subconsciously and instantaneously and incessantly, to create a fully functional and richly layered hallucination that serves as reality. And it’s impossible to do this neutrally, without bringing ourselves into the creation. We simply cannot be in the world without being sculptors, because our world is itself a sculpture we make in order to live in it. It is of necessity an imaginative co-creation.

And when we pretend that we’re not co-creating the world as we move through it—when we subscribe to the jigsaw-puzzle model of reality—we enshrine at the base of all our operating and decision-making, societal and individual, the least imaginative, least expansive, least life-giving interpretation of the infinite, beautiful strangeness we swim through, then tell ourselves (or are told) that this impoverished vision is the incontrovertible reality. And that’s how we end up with the fallacy that human intelligence is comparable to or replicable by AI, and besides that with coup by tech broligarchy and social-political-economic collapse and ecological collapse and this sense in so many if not most of our lives that we are missing the point of life itself. And all of it built on a fundamentally broken idea of what reality is.

Right now, as we’ll see, we are butting up against the limits of what materialist science can tell us about the nature of the universe. In my view, this means that sooner or later, the ideological, culture-wide mistake into which materialist science has been distorted—that the full truth of the world can be known through supposedly objective experimentation and the rational mind—will soon be debunked, if that’s not happening already. The days of this ideology of scientism, of the jigsaw-puzzle model of reality, are numbered. So what’s the opportunity here? And how do we make sure the reappraisal of materialist science doesn’t degenerate into the kind of material-reality-is-a-scam, coffee-enema, give-me-$500-to-read-your-aura-on-Zoom, spiritual-bypass bullshit that is so rife right now? How might we seize this opportunity to live into a base agreement about reality, and therefore a culture, that are much more life-giving than we in the West have known for at least 500 years, if not a couple of millennia?

Let’s go.

***

What is it that separates you right now from, say, the south pole? Most of the readers of this Substack are in the UK and the US, so, if you’re in London, it’s about 9,800 miles. If you’re in New York, it’s closer to 9,000. You get the picture.

But what if I told you that actually, the south pole isn’t distant from you at all? And not just the south pole but everywhere you think of as distant, as well as all the far-flung people you love? That in fact, the space between you is an illusion?

This isn’t just a thought experiment or some sentimental image. It’s what physics is telling us is the structure of our world. For a while now, physicists have known that space is an illusion. Of course, that’s not to say that you’re actually standing at the south pole right now, and you simply haven’t noticed it. It means that whatever’s separating you from everything that feels distant is actually something other than space. Some other kind of energy or quality that originates in another dimension of reality, which we can’t fathom in its full, original form, here in our three-dimensional realm.

It might be helpful to use the thought experiment of flatlanders: two-dimensional beings who live in a two-dimensional world, in which everything is laid out on a plane. If those flat beings and their two-dimensional world were positioned as a plane inside our three-dimensional one, they’d experience our three-dimensional reality very differently to the way we do. They’d sense it as strange interruptions flitting across their plane momentarily before disappearing. Naturally, they would come up with some explanation for what was going on, but how could they possibly intuit the fullness of what we’re up to here in three dimensions? From those two-dimensional flashes, how could they know about ballet and music (since sound relies on three-dimensional vibrations) and clouds and rivers and all the rest of it?

In the same way, physicists are telling us that what we experience as space originates as another force in another dimension of reality; it’s just that in our three-dimensional world, we’re only able to fathom it as space. In the words of the science writer George Musser: “Locations that seem far apart can lie right on top of each other. What appears to be spatial distance is in fact a distance in energy.”

Physicists have been arriving at these conclusions for a while now—I’m late to the party. I first wrapped my head around all this a couple of weeks ago while driving on the motorway (on a journey that sure as hell seemed to involve crossing an annoying amount of real space), and I had to pull my car over to blink and breathe for a bit and sort of stare idiotically at the backs of my hands. I was listening to Lights On, a new audio documentary by writer and researcher of consciousness Annaka Harris, which journeys into the idea that consciousness might be fundamental—meaning, felt experience might be the base element of the universe, preceding even space-time. (Hat tip here to my friend Bert, who recommended Lights On. Thanks, Bert!)

Now here’s the part I wanted to get to. Having established that space is an illusion (you know, no big deal), Harris goes on to say a couple of things that made my ears prick up, even as my brain was leaking out of my eye sockets from trying to understand the science. Here’s the first, which she says in conversation with George Musser:

[I have a] very strong intuition that drives a lot of my interest, and it seems to be confirmed as I’ve worked in the sciences, that there is so much right here with us. It’s all right here. We just are very limited in our ability to perceive it and access it, based on the limits of the human brain and what we evolved to be able to perceive.

Then, a few minutes later in the same episode, she says this:

If space is not fundamental, it seems like there’s a sense in which everything, at least the stuff that we can potentially interact with [as opposed to e.g. a pebble on a moon on the other side of the universe] is actually right here, in a sense. Because there is no space. And the space we perceive between everything is just a hint of some more fundamental structure or force or law of nature.

This framing made me sit up straight, because I’ve long had this same intuition: that in some way, everything is right here. (We’ll get on to what I mean by “everything” in a moment.) And that the scale and dimensions of our experience are determined by our perceptions; by what we are able to pick up from all the everything.

And of course it’s not just me. I’ve found this intuition reflected everywhere in the texts of mystics and artists who have spoken about their imaginative and meditative processes. For instance, here’s modern-day mystic Cynthia Bourgeault in a book I quote often and highly recommend, Eye of the Heart:

Virtually all spiritual teachers in all traditions have insisted that the “higher” (i.e., less dense) realms are not somewhere else but within—already coiled inside us as subtler and yet more intensely alive bandwidths of experience and perception. The reason we do not typically notice them is that the laws governing any realm are generally too coarse to allow the penetration of those finer vibrations emanating from the next realm “up” into its normal sphere of operations.

Here’s another lovely image from Bourgeault:

Impressionistically, the imaginal penetrates this denser world in much the same way as the fragrance of perfume penetrates an entire room, subtly enlivening and harmonizing.

Or there’s this familiar banger from William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell:

If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.

OK, OK, you might be thinking. Surely we’re talking about different things here. Harris is talking about demonstrable findings about the structure of the material universe, whereas Bourgeault is talking about a divine realm of vastly expanded potential, an ineffable field that is the causal origin of events in the material world. Harris is talking about the nature of space and the possibility that all the physical objects in our known world are in some way right here around us, whereas Blake is talking about his innate capacity to see spiritual emanations of items in the physical world.

I’d say two things in response to this distinction, in this quite strange conversation I seem to be having with myself in your inbox. First, it does nothing to negate the core idea that there is far more to material reality than meets the eye, and that our capacity to encounter that something-far-more is intimately bound up with the limitations of our perceptive apparatus. Second, I’m not convinced that the undetected presence of a kind of material infinity, and the existence of an ineffable realm of infinite possibility, are actually different things. If the universe is infinite, and there’s a possibility that everything in it might be here with us all at once, but beyond perception—isn’t that the same as the realm beyond our perception holding infinite possibility? (And in fact, Harris herself arrives at a similar question in a later episode of the documentary.)

I don’t know the answer, but I think it’s worth staying with the question, which boils down to: If space is an illusion, and everything is right here, what exactly is it that’s right here? What’s the unseen stuff we swim in all day? And how can we best relate to it?

The whole arc and effort of Harris’s documentary is to pursue these questions through the research findings of materialist science. She wants rigour and she wants empirical evidence. And yet the journey brings her to the edge of what science can tell us. Here’s cognitive psychologist and scholar of consciousness Donald Hoffman, explaining in one episode of the doc how at a certain point, because we have no way to test what’s going on in the expanded or alternate dimensions, physics—the study of the fundamental matter of the universe—has to give way to mathematics, a much more theoretical pursuit:

[Physicists are] hitting a very interesting wall. Because [...] all the real physicists understand, it’s over for space-time. It had a good run for several centuries, but it’s over. The only flashlight that they have to peer in the darkness behind space-time, to try to figure out what’s deeper, is mathematics.

But if you ask me (not that anybody did), even maths will only get so far in telling us about those expanded dimensions of reality, because this is at base simply not a problem for maths, or for science as we know it either. In fact, Harris acknowledges this herself. Towards the end of the documentary, when she concludes that it’s worth working with the premise that felt experience is the most fundamental stuff of the universe, she notes that this would require humans to develop a new kind of science. After all, the whole discipline of science is founded on the assumption of objectivity; on the attempt to establish through observation and experimentation the full truth of “things as they are”, to use Enlightenment bigman John Locke’s phrase. But if the root of all things is simply felt experience, then there is no solid, external “things as they are”. There is only the forever dance of experience, feeling itself, and changing through the very act of being felt, being perceived. (I feel its pain. Nothing more destabilizing than being perceived.)

And so what we need now, Harris suggests, is new technology that is able to incorporate this primacy of felt experience into empirical scientific methodology. She suggests some sort of neural tech that could give the wearer an accurate experience of what it is to be another person or non-human being. This way, she suggests, we could begin to build up a picture of the infinite perspectives on all this felt experience that together create what we call reality.

At this point, I laughed aloud in my car. (I think if we’ve learned anything in this essay, it’s probably, don’t get in a car with me.)

And truly, I don’t mean that to sound mocking. I thoroughly enjoyed and was deeply inspired by Lights On. Annaka Harris is an insightful guide to this emerging picture of reality.

But it’s so funny, the lengths we humans will go to to keep our left brains in charge. To cling to the fiction that we’re living in a jigsaw puzzle; that there’s some way to find certainty, to locate the picture on the box that will give us the answers.

Because if reality is just a formless felt experience, inventing ways to feel itself.

And if to be incarnate is to briefly be a way the universe experiences itself.

And if what we’re looking for, in order to expand our understanding of all this felt experience that constitutes reality, is a method that enables us to enter into the experiences of others—human and nonhuman and even not-yet-incarnate, even taking the form of ideas—deeply and fully and with devoted rigour, and begin, from those intimations of felt experiences from beyond the self, to paint a picture of a possible world, a possible whole.

Then we already have the method, the technique, and the technology we need.

We’ve had it all along.

It’s called art.

It’s called imagination.

It’s humanity’s age-old, incomparable, perfect method of sharpening our perceptive capacities; expanding our consciousness to intuit felt experiences and realities beyond the self; and committing, rigorously, to bringing those intuitions through into material reality in the most illuminating way possible.

I want to be clear here. I’m not saying that we should abandon materialist science. I’m not saying that it’s been useless all along. I’ve taken antibiotics. I’ve eaten commercially grown food. I’ve flown on planes. I’m using a computer right now. I know my debts.

I’m saying that the scientific method should only ever have been one of our ways of knowing the world.

It can only tell us about a certain level of experience in the material world, in which so-called objects appear to be objective. To try to apply it to divining the felt experiences of other beings and other realms is a category error, to use the phrase

uses so brilliantly in his book At Work in the Ruins.If we want to know about the more-than-material world—about the infinite and ineffable realms in which everything appears in its original form, meaning as a temporary tension in consciousness—then we don’t need to develop new technology. We need to begin to trust our other ways of knowing.

Because here is a secret that’s not so secret to anyone who’s read this Substack before, or been following the last few decades of developments in archaeological research: art did not begin as a practice of generating products in order to make a buck. It began as a practice of cosmology. The earliest artists of our species, who made prehistoric cave paintings and sculptures, seem to have worked by expanding their consciousness in order to enter into felt contact with expanded realms of reality, and then brought intimations of those other realms back to our material world, in the form of paintings and sculptures. In the words of archaeologist David Lewis-Williams, “The images were not so much painted onto rock walls as released from, or coaxed through, the living membrane […] that existed between the image-maker and the spirit world.”

Humanity’s first painters were our first and to my mind best-ever cosmologists, best-ever explorers of the full reaches of the universe, because their method of cosmology presupposed the truth towards which physicists now seem to be inching: that we can’t know anything without felt experience and without creativity.

And this process has been going on ever since: artists coaxing deep and previously unseen truths about the universe into their perception, then expressing those truths the only way they can be expressed: as works of art, of imagination, that do not try to pin down but rather keep unfolding more creativity because that is the nature of reality itself, to keep unfolding more creativity.

I think of my teacher Alice Oswald turning herself into a river and all the voices that make it, for her book-length poem Dart. I think of Shakespeare absorbing the voices of the living being that was England in the sixteenth century, and producing plays that incarnate that being, that England, on the stage. I think of the Ancient Greek playwrights who invented the enduring art form of theatre not by puzzling out their plots, but by transcending the bounds of self at festivals in worship of Dionysus, and receiving intimations from the gods that could only be expressed by inventing an entirely new form of art.

I think of this poem that is in fact a bird:

Or this painting that contains the kind of elemental energy most humans through history have known as a god:

Or this painting that is a country at a mythical moment in time, a fleeting but eternal epiphany of integrity:

And I know that we have and have always had as full a guide as we could ever need to the expansive reaches of our universe, and to what it is to be alive.

I understand why it might feel dangerous to suggest that art is our real guide to reality. All these hundreds of years into the mistake that is the dogma of scientism, our culture fundamentally misunderstands art and imagination. As I’ve already observed, they are seen as luxuries; as nice extras. As frivolous acts of fanciful invention. And meanwhile, we have a serious problem on our hands, in the form of this backlash against the Enlightenment that has people drinking bleach and getting sucked into cult-like “healing” methods and who knows what else.

So I want to be very clear. The kind of imagination I’m talking about is not about plucking ideas out of your own unresolved ego and passing them off as truth. “Passing things off as truth” isn’t the objective at all. That’s the whole point.

The kind of art and imagination I’m talking about begins with deep and devoted attention to the world around us. Truly, the artists I know in all disciplines are the most devoted and rigorous people I’ve ever met, engaged in a ceaseless, life-and-death effort to observe the world and the ways it meets them, because this is the raw material of their craft, and then to bring what they observe through in the most illuminating and beautiful way possible.

But the goal of this effort is not to establish objective truth, much less hoodwink anyone with it. That’s not how the imaginative sensibility is oriented. Unlike the scientific sensibility, it doesn’t seek to pin down or puzzle out, because to live in the world imaginatively is to know, on some level, that there’s no answer. No box somewhere that will show you the picture you’re trying to piece together. To live this way is to recognize that all attention is co-creation; that we bring the world forth by beholding it. And if that’s the case, there is, ultimately, nothing to pin down; there’s only the continued creation.

Here’s

, in his brilliant, beautiful book Imaginal Love [bolding mine]:Any reality supposed to be literal: this fact, this rock, this Book, this Truth, anything we try to pin down as stable, universal and immutable—the rock-solid facts of existence—these are all abstractions. The literal is always abstract—because reality is so much more than we can ever know or experience or imagine. Nothing stays put—everything real, embodied, concrete, ramifies, multiplies, sends out roots and shoots and explodes into images. There is no end to telling the stories of persons and things. Only the fictive is concrete. That is why there is no end to the telling of stories. Of people, of things. Fiction, myths, fairy tales, gossip and rumors—these are the fictions of persons. The astounding richness of the stories science tells us, and continues to tell us seemingly without end—these are some of the fictions of things. Nothing stays put.

And this is why belief is such a dangerous thing. […] Belief wants to know; the imagination wants to hear more stories, to unfold the endless tale of reality.

And the most beautiful thing is, you’re already doing this. You already know how to use your imagination, how to sculpt reality, because you’re doing it all day every day, without even noticing it. It’s the first thing you learned as a baby.

The key to turning that constant and automatic act of co-creation into an art is simply to slow it down, become conscious of it, and take some joy in it. Have the audacity to intentionally create the most beautiful sculpture you can.

Because everything is right there. All the clay you could ever dream of, and more. And reality is not a jigsaw puzzle but a sculpture. Which means the task of life is not to pin down or puzzle out. It is to love the ceaseless creation.

Wow! Another wonderful essay! How do you keep doing it?

I wonder if the body itself is a portal for the imaginative realm? We focus so much on the products of the hands, the information from our eyes and our mouths, but what if we could listen to the more subtle energies flowing through us through the other parts of the body? Would that be the start of cleansing the doors of perception?

So so brilliant Eleanor. The metaphor of how we've flattened and disintegrated and simplified the process of creation -- here, lets outsource the complexity of animating life force into little bits with uniform shapes that fit into each other on a two dimenisional plane no less!! Even our metaphors have become so anemic. We can start to re-member ourselves and our talismanic relationship to consciousness by starting to breathe life into these imaginal fields. puzzle piece into canvas, then canvas to sculpture, then sculpture to ritual theater.