Memorising poems and stories is magic that remakes the material world

On Dante's Inferno, indigenous songlines, and shifting baseline syndrome

Hello!

If you want a mental image here, please picture me emerging, blinking, into the autumn. I spent most of the summer consumed by hyperfocus, working on a book proposal, but now it’s (nearly) DONE and I get to chat with you lot again. Hooray!

Aside from proposaling, I’ve been having my mind blown by training my memory as an act of imaginal resistance. Here’s a little essay—still warm from the oven and rough around the edges and any other mismatched imagery you care to throw into the mix—about why I think recovering memory is such an important part of this moment.

x Ellie

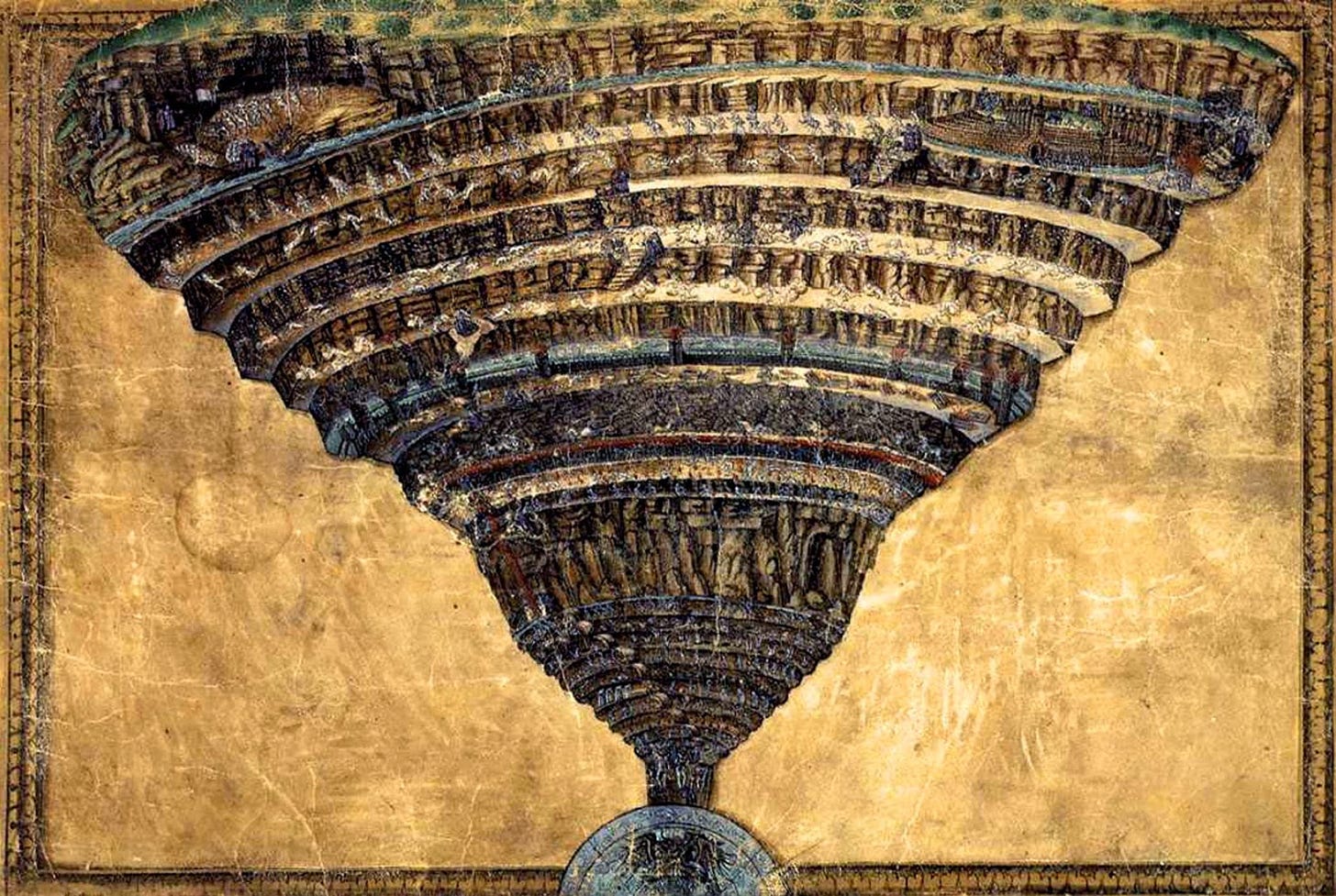

I’m memorising the first canto of Dante’s Inferno. Yes, I’m a nerd. But also, this is my pledge for the memory club that’s come together through this Substack—a club that’s investigating whether memory can be a form of resistance. (By the way, if your instinct is to click away from anything about memory because you fear that yours is crap, please don’t! I am far from a memory athlete. In fact, I’m in long-term recovery from alcoholism, and I did my brain and my memory some real damage, back in the day. And I’m finding that even I can nurture my capacity to remember, to quite an astonishing degree. All to say: if you struggle with memory, you’re not alone (in fact I think atrophied memory might come hand-in-hand with modernity), and it is trainable, and training it might be surprisingly important. OK, enough brackets.)

The premise of the memory club is that bringing stories and poems to live inside our bodies might be an act of resistance. Originally, I thought of this as a resistance against AI—against the invitation to outsource our very thinking to the large-language models (LLMs) of artificial intelligence, which are essentially externalised memory banks. By internalising the things we wanted to know deeply, I hoped we might bring at least some of this meaning-making back into human hearts and heads.

But as I memorise—as I bring the Inferno into my body—I’m beginning to believe the scope of the resistance might be bigger than I’d thought. I’m beginning to think that the loss of human memory that has come with creeping modernity—the way we’ve outsourced our remembering to technologies beginning with the written word and coming right up to AI—has constituted an inner desertification that has helped us to wreak the desertification, the stripping of wildlife, in the outer world.

Back in the mid 2010s, there was a lot of talk about the environmental concept of shifting baseline syndrome. As far as I remember, it was George Monbiot who really championed the idea, helping us to see that each generation experiences the world it’s born into as normal, as the baseline—and in a world that has been rapidly losing wildlife and healthy ecosystems, this means that generation on generation, we are normalising staggering losses. “We’ve lost almost everything, and yet we regard that as normal and natural,” Monbiot said in an interview in 2017. And this doesn’t stop with environmental degradation. “I’ve used it in the political sense,” Monbiot says in that same interview, “to say: Why do people accept tyranny and despotism and the erosion of democracy? It’s because you normalise whatever surrounds you.”

I’m only at the start of my memory practice, but it’s already becoming clear to me that we also normalise whatever is inside us—meaning, the norms we receive about what a human is and needs to know, and even the metaphors and imagery we use to comprehend and describe our inner lives.

We are a storytelling species. Once upon a time, every human would have carried inside themselves a polyphony of stories and poetry. They would have brought plurality of voice and view into their flesh. Today, we’re exposed to more writing, more art, more viewpoints than humans living at any other time, but it’s all external. We don’t take the trouble to bring it into our flesh anymore, even though the dimensions of our inner landscapes have never been more ample than in this therapised age. (And I don’t mean to be totally dismissive; I’ve had years of therapy. It’s been tremendously helpful. But in my experience, there are some problems baked into the form. And a certain tendency towards solipsism might be one of them.)

In short, we’ve internally monocropped ourselves, and—though this is an intuitive leap—my gut is telling me that that has made it far easier to monocrop the outer world. The singleness of view and voice becomes singleness of purpose and deed in our outer dealings. And in a living world that’s relational and ecological in structure and form, this kind of solipsism is always, ultimately, death.

If that all sounds a little vague, let me get more specific. We’re not just a storytelling species but a nomadic one. It’s in our evolutionary makeup to learn landscapes, and to stitch our knowing to them. This aspect of humanity finds its most famous expression in the songlines of indigenous Australian cultures—routes through the land that stitch the material realm to the Dreaming, and hold a wealth of mythological, geographical, and cultural storying. But there’s some version of this in every oral storytelling culture, which is to say at the root (however forgotten) of all of humanity. In our earliest days, humans made meaning by moving through the land, receiving its stories, and embroidering the insights of eternity onto the mountains and rivers and forests, in the form of stories and poems. These stories and poems were passed on, and their truth lived in the encounter between landscapes and humans.

And this evolutionary heritage is still inside you now. In our memory club, we’ve been studying the classics of memory literature—the great works written over the past half century or so, which have investigated and begun to resurrect this art so long lost to the modern mind. You’ve probably heard of some of the central insights of these memory classics. The most famous among them is the memory palace: the practice of memorising something by turning it into images, which you then imaginally stow around a place you remember very well, like your childhood home. To remember the passage, you imaginally walk around the palace, retrieving the images. This practice rests on the insight of the Ancient Greek poet Simonides, who realised (through a pretty wild event that I won’t go into now) that the human mind is primed to remember images and physical locations better than anything else.

Why? Because this is what a human is: a nomadic, storytelling being. A creature evolved to move through the land, listening for stories, then telling those stories back to the places they were heard from, generation after generation. We are walking story maps.

Which means that internal and external geography have always been critically linked. I don’t have songlines for my current home of southwest England, nor for the region I grew up in, the southeast of England (though in the southwest in particular, the folk revival is restoring some of the polyphony of land). But I do know that when I memorise the opening of Dante’s Inferno, I am enriching my inner world with a forest—the dark forest the poet awakens in to find himself lost. And I know that when I take that imaginal, remembered forest—a forest co-created between me and Dante and rich with its own presence—into the real forest near my home, my experience, my encounter, is deeper and wider and fuller.

An inner landscape that’s barren of voices and places means a much shallower encounter with the outer land. And when the land appears to us in this impoverished form, it’s much easier to destroy it in service of our own will.

I spend a lot of time thinking about the Ancient Greek word for truth, aletheia. The “lethe” in the middle is the River Lethe that runs through the underworld—the river of oblivion or forgetfulness. And the prefix “a” means “not” (as in “asexual”). So for the Ancient Greeks, truth wasn’t a series of facts. It was a moment of remembering. Of emerging from oblivion and remembering the fullness of the world, with the fullness of yourself. It was always an encounter.

So how do we encounter a full world, in its fullness? A lot of it comes down to attention and awareness in the moment. To not spending our lives zoned out. But when we do manage to be present, what we bring to the moment matters too. We’ve all had that experience of meeting a person and feeling that we’re simply missing each other—that we have no frame of reference, no perceptive apparatus, for who and what this other person is in the world, and so no way to really meet them.

By externalising our memory of stories and poems to books and tech, and desertifying our memories and imaginations, we are doing the same thing in our encounters with the living world.

And that is why I believe reviving the ancient memory arts is an act of resistance.

xx Ellie

PS. This wasn’t a plug for the memory club! It’s just what I’ve been thinking about. But if it’s inspired you to join, you can still do so by signing up to this Substack as a paying subscriber. And you can read more about the club here.

Beautiful Eleanor! I agree with so much of this! For me, singing folk songs is a parallel lineage that I have drawn from in my learning, alongside reading books. Folk songs are an oral form & the singing of them is an act of memory & recall, so I have been privileged to experience & observe memory in action a lot. The architecture of memory is universal in humans: it was the way important information was transmitted down through time for millennia. However, it's also a set of muscles, that atrophy from disuse. I know people in their 80s with 500 songs stored in their head. And I know people in their early 20s who don't dare to even attempt to remember. (The old people are proof of what's possible! Be more like them!)

Some things I have learnt about memory:

Writing down is good for learning, listening repeatedly is good for learning, reciting or singing is good for learning. These are all aspects of memorising practice.

Reciting or singing while walking is particularly good. A lonely beach or hillside means you can really get into it with nobody watching.

Rhyme, rhythm, & repetition are memory aids: this is why old ballads & songs are structured the way they are. They also grant breathing space for the mind: while you are repeating an 'easy' bit (a chorus, a response, a repetition, or some nonsense sounds) another part of your brain can be remembering the 'hard' bit that comes next.

You can rely on the paper while you are learning, but at a certain point you have to throw the paper away, jump in the deep end, & try to remember. Otherwise you will never prove to yourself that you can do it. I also think that at a certain point the paper becomes a crutch: if you have the option of it, you will be tempted to look at it, rather than attempting to remember.

One interesting thing with folk singing is there can be a 'group memory', where if you forget someone else remembers, & can prompt you. I just got back from a festival where we had many singing sessions; some people sang from handwritten books of songs (mostly newer singers, just learning) but many of us sang purely from memory all weekend.

I have a lot of visual metaphors for how it feels to remember. To remember a song is like pulling a string. But there is also the sense of walking a pathway. I have heard it compared to a heap of stones. Learning a song can be rote but often it is not, often there is a story inside the song: story makes remembering easier.

Once something-memorised is in long-term storage it can be pretty fixed (as in you will be able to remember it more easily), but generally speaking, you do need to keep re-polishing the silverware you have stored away: you do need to take things out to keep them fresh.

Put things in your mouth, put them in your head-bone, they can't take that away! Store up treasure that goes with you always!

Don't know if I've shared this with you before but... Walter Benjamin on the power of copying out texts. Not quite memorising but I think you mentioned it as a medieval practice in an earlier piece? I have 500+ money quotes on my old blog and copied each of them (i.e. typed them in by hand). Benjmain's quote made sense of that for me.

https://jonone100.blogspot.com/2015/09/money-wisdom-373.html

I've long had the desire to memorise the opening of Under Milk Wood. If you keep writing so persausively I'm going to be adding that as pledge to the Book of Horkus next January and will be forced to learn it for fear of upsetting the Gods (and Daisy)!